Jesus's Humor: Part 3 - Setups, Pauses, and Punchlines

A large number of Christ's verses can be broken down into the standard comedy form of the "setup," "punchline," and "tagline." The setup creates expectations. The punch line confuses those expectations and generates a laugh. The tagline is a second punchline to keep the laughter going. Pauses are used between each of these components to get that audience time to get it. A very similar form is used in Jesus’s drama. But when being dramatic, Jesus’s setup creates tension, the pause extends it, and the punchline relieves it.

This structure is apparent in Greek, but it is usually lost in translation because the words are moved around, often putting the punchline before the setup. The fact is that translators are translating his words to get to a religious point, not capture his humor or comedy.

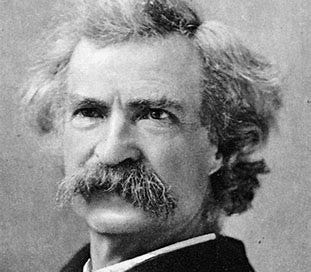

Of these, the pause is essential, but it cannot be captured in writing. The humorist Mark Twain observed, "No word was ever as effective as a rightly timed---pause." We can only spot places where Jesus probably paused in delivering his lines because they sit between the setup and the punchline, which is often one Greek word. The pause works in humor because it gives the listeners time to make the false assumptions that set up the surprise that creates a laugh. Or it extends the tension of a dramatic situations.

Imagining the Pause

Again, Jesus's "body of work" was spoken, not written. Punctuation, even spaces between words, didn't exist in written Greek at the time. The stories I tell in my upcoming novels try to capture how the words would be spoken, which includes the pause. They also assume that Jesus was interacting with his audiences, not just preaching to them.

Word order is what makes the pause work. Though technically, Greek uses a different word order than English, humor changes the common word order because it has to put the surprise at the end, whether the surprise is a noun, verb, adjective or adverb. Keywords at the end of a Greek sentence or phrase are unusual since Greek word order normally puts the most important words first, not last. However, the very fact it is unusual helps its humor, since humor depends on surprise.

Translation almost always changes the word order of the Greek. Often this is done to simplify meaning, hiding any potential double meanings. Religious teachers don’t like the suggestion of double meanings. The meaning that the translators think is important, given their dogma, is emphasized. This usually isn't the funny one. Of course, wordplay based on word sounds is lost entirely. Still, let us start with some easy examples, starting with the basic pause to create suspense.

In the example below, I try to show why that imagined pause is sometimes necessary for the humor to work. Even though, in this example, Jesus is simply starting a story, not making a joke.

An Example of Shifting Meaning

Word order is crucial to humor. Jesus often organizes words to take his listeners on a surprising journey, with the biggest surprise at the end, after a pause. These journeys do not necessarily add up to a joke. Sometimes, they are just playing with listeners’ assumptions about what is coming next.

For example, at the beginning of the Parable of the Lost Sheep, Matthew 18:12, .the second clause has only six words in Greek, ἐὰν γένηταί τινι ἀνθρώπῳ ἑκατὸν πρόβατα. As those six words are spoken, however, the listener must constantly change his or her assumptions about what is being said. For the listener, Jesus’s words offer a series of surprises, a roller coaster of shifting meanings, offering multiple opportunities for pauses adding to the audience’s suspense and confusion.

The verse starts simply, "When it becomes" ean ginotai (ἐὰν γένηταί), but, though the verb that primarily means "becomes," it has many different meanings—”becomes,” “happens,” “is produced,” “is owned,” and so on— depending on the context. By starting the sentence with the verb, more common in Greek than English, the context is hidden. Listeners only know that the subject is singular because the verb refers to a singular subject. A pause here forces the audience to think about those possible meanings. However, the common Greek order leads the listener to expect the subject will come next.

But the subject doesn’t come next. This verb is followed by an indirect object "to/by some man" (τινι ἀνθρώπῳ). This limits the meanings of the verb to two possibilities: "produced by some man" or "belongs to some man." depending on the subject and whether it is something a man produces or owns. The listeners must again wait for the subject, so they are still in suspense. This is a good place for another pause.

Then comes the word, hekaton, (ἑκατὸν) which also has two meanings. It can be the number, “one hundred” or an adjective meaning meaning “far shooting.” It doesn't seem to indicate a number relating to the subject, because the verb’s subject is singular. A “hundred” is plural. Like all numbers, it doesn’t change form to tell us if it used to describe a subject or object. However, “far-shooting” is singular, but it doesn’t its form is that of an object not a subject. So, at this point, the audience is doubly confused. Another good time for a pause.

Then, finally, the plural subject noun appears, "sheep," probata, (πρόβατα), which, though plural matches, the singular verb because of a quirk in Greek. Greek plural neuter nouns, that is, “things,” are treated as a single conglomeration for ownership. The word probata is neuter, being “things” owned.

So, as the final word is spoken, the meaning of the second word, the verb, ginotaiί, and the fifth word, hekaton, is finally revealed. The verb must mean "belongs" because sheep are owned, not produced, by some man. The sdjective must be “a hundred.” Everything works out as perfectly grammatical Greek, but what a wild ride for the listener.

And it is all lost in translation, but only because the translators don't care about the humor, but also because they want Jesus’s words to be simple and easy to understand. For me, this stuff is totally fun to translate. The ending of this verse is also great, at first saying the exact opposite of what it means. See this article about it to learn more about this great verse.

Conclusion

In the next couple articles, we will dissect other verses to demonstrate the use of pauses and other techniques in Jesus’s humor. The truth is that many, many of the phrases with which we think we are familiar, often do not even come close to what Jesus actually said much less capture how he said them. To paraphrase Jesus himself, “We hear but we do not listen.”